LOCAL LAW 154: NYC Building Electrification Explained

Written by Brooks McDaniel, Senior Vice President, Building Repositioning, STO Building Group

Buildings are the largest source of greenhouse gas emissions in New York City. To reduce manmade greenhouse gas emissions, NYC City Council has banned the burning of fossil fuels in any new building or any building undergoing a major renovation, starting in 2024.

The bill prohibits the combustion of “a substance that emits 50 kilograms or more of carbon dioxide per million BTUs of energy in any new building or any building that has undergone a major renovation.” This includes natural gas, fuel oil, coal, and other fossil fuels. New or substantially renovated buildings must rely on electricity for heat, domestic hot water, and domestic cooking. A similar bill has been proposed by NY state lawmakers, and legislation is in the works in other cities and states around the country.

Will this bill reduce greenhouse gas emissions?

Eventually yes, but it will take time. Currently, 85% of NYC’s power is produced from burning fossil fuels, with only 15% coming from renewable sources. The reverse is true across NY state, with 88% coming from clean resources, but the existing transmission lines do not have enough capacity to bring much of this clean energy to the city. So, for now, NYC will continue to rely on its 24 power plants, which burn natural gas and/or fuel oil.

However, the city has committed to transforming NYC’s electricity grid into one powered by zero-emissions resources by 2040. To do this, there are plans in place to build large-scale offshore wind farms, extensive upstate solar arrays, new transmission capacity, as well as large energy storage facilities to add resiliency and redundancy to the grid.

Can the grid handle it?

Building electrification poses no immediate risk to the grid. NYC’s winter power demand could grow by 42% before exceeding summer peak demand. A detailed study of grid readiness is due to be released by mid-2023.

When does this law take effect?

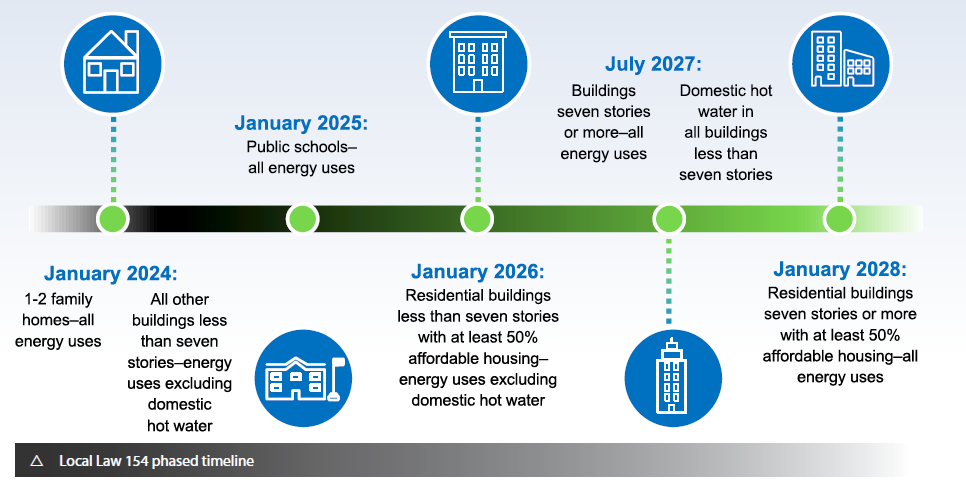

The implementation dates are phased to allow time for the market to ramp up with more products, training, and design strategies.

How will I heat and cool my new building?

Air-source heat pumps will be the system of choice for heating and cooling most large buildings. These electrically powered units are emissions free and work in a wide range of exterior temperatures. A four-pipe distribution system allows simultaneous heating and cooling of different zones of the building and allows for energy recovery on the return water which enhances the system efficiency. Electric heat pumps operate at lower temperatures than traditional boilers and chillers, typically 95°-105° for heating water and 55° for chilled water. The lower water temperature requires the use of larger fan coils than high temperature systems.

A large building will have multiple heat pumps located either on the roof, or on screened open-air mechanical floors (breezeways). Skyscrapers taller than 500ft are likely to require two or more openair mechanical floors due to the size and number of heat pumps, and the space restrictions on a tower roof. There will be some space efficiencies created on occupied floors since there will be no boiler flue rising through the building.

The installation cost will be higher than a building with a gas-fired boiler, since large heat pumps are more expensive than traditional boilers. However, prices are likely to come down in the future. There is extra cost associated with the additional plumbing related to thermal loops, and due to the need for the larger fan coils as noted above.

Lastly, the building’s electrical power requirements will be at least double that of a building with gas boilers, which will also increase construction cost.

The operation cost will be roughly the same as a building with a gas-fired boiler currently. In the coming years, gas-fired and steam boilers may become more expensive to operate as the city switches over to electrified buildings. Utility costs for gas and steam are expected to rise due to high overhead costs with fewer customers. And building owners who don’t switch to all electric heat pumps will be penalized for excessive emissions starting as soon as 2025, due to Local Law 97.

What other heating and cooling systems could I consider?

For buildings less than seven stories, variable refrigerant flow (VRF) system is a viable and increasingly common alternative. These are smaller than air-towater heat pumps and circulate refrigerant from a series of roof-mounted compressors to the interior areas for heating and cooling. Each unit is individually piped to the zone being served. VRF systems are far cheaper to purchase and install than airto-water heat pumps, however, they are likely to have a shorter lifecycle due to increasing restrictions on refrigerants that are harmful to the environment. As the current refrigerants are phased out, the entire system will have to be replaced.

Lastly, air-to-air heat pumps are likely to be a common supplemental system in large buildings for tempering incoming air for dedicated outside air systems (DOAS), as required by NYC building code.

How will I make domestic hot water?

Traditional electric hot water heaters using resistance coils are common in single family homes but do not exist on larger scales for multifamily residential buildings or large commercial buildings.

Air-sourced heat pumps and water-to-water heat exchangers will be the common solution for domestic water in larger buildings. Additionally, some portion of domestic hot water capacity could come from a water-to-water geothermal heat pump, although this is likely to be limited.

Lastly, if I file a permit for my new large building prior to the deadline, can I use gas?

Technically, yes—but there is a risk. The lifespan of a building is longer than the systems within it. When you renovate your building in the future, you will likely be required to convert to electric heating and cooling. Many of our clients are already making the switch in advance of the deadline.