Special Joint Episode – TSX Broadway: Raising History in Times Square

TSX Broadway is being transformed into an unprecedented, entertainment-driven destination that will redefine how people engage with Times Square. In this special joint episode with The Anti-Architect Podcast, Pavarini McGovern Vice President, Jason Vesuvio teamed up with Christian Giordano, President & Co-owner of Mancini Duffy, to tell the story of this iconic project—including lifting the historic Palace Theatre 30 feet in the air.

Featuring insights from Bill Mandara Jr., CEO and Co-owner of Mancini, Tony Mazzo, President of Urban Foundation/Engineering, Benjamin Alper, Associate Principal of Severud Associates, and Joe Levi, Project Manager at Pavarini McGovern, and co-hosted by Jason and Christian, this episode covers the who, what, when, and why of the TSX Broadway theater lift, as well as what’s next for the team as construction continues.

CO-HOST

Christian Giordano

President & Co-owner, Mancini DuffyView Bio

CO-HOST

Jason Vesuvio

Vice President, Pavarini McGovernView Bio

GUEST

William Mandara Jr., AIA

Chief Executive Officer, Mancini DuffyView Bio

GUEST

Tony Mazzo

President, Urban Foundation/Engineering, LLCView Bio

GUEST

J. Benjamin Alper, PE, SE

Associate Principal, Severud AssociatesView Bio

GUEST

Joe Levi

Project Manager, Pavarini McGovernView Bio

Christian Giordano (00:00:09):

Hello, Anti-Architect and Building Conversation podcast listeners. I am your host, Christian Giordano from the Anti Architect Podcast and Mancini Duffy.

Jason Vesuvio (00:00:20):

And I am your co-host Jason Vesuvio from the Building Conversations Podcast and Pavarini McGovern, which is an STO Building Group company. Today we have a special joint episode of our two podcasts. We’re going to dig deep into one of the most fascinating construction projects maybe ever.

Christian Giordano (00:00:37):

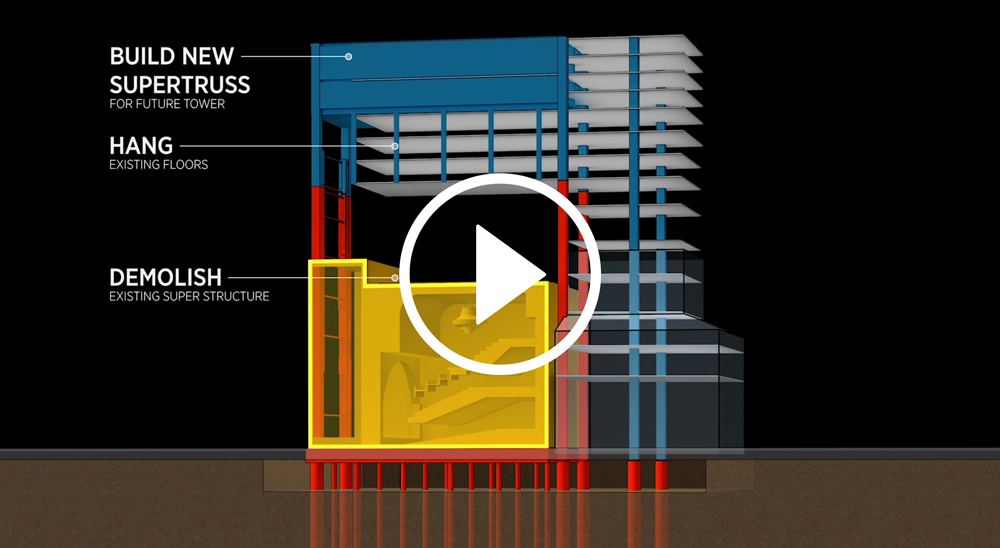

Yeah, I agree. I’ll give you a quick overview of TSX Broadway. It’s located at 1568 Broadway and 49th Street in the heart of Times Square. And at this point, as of today’s date, November of 2020, it is about 80% complete. It’s located on the busiest corner of the most heavily trafficked public space in the world. When complete, it will be a one-of-a-kind entertainment venue, hotel, retail experience. And of course, it has this landmark Palace Theater. It’s 48 stories tall, 581 feet to the top of the crown from the sidewalk. 16 of those floors are old, what we call retainage slabs from the previous DoubleTree Hotel. We’ll get into a little bit of that and how that works.

Christian Giordano (00:01:37):

585,000 square feet in terms of square footage with about 100,000 square feet of retail. It’ll have one of the most unique LED facades in the world with the world’s largest digital doors and a performance stage behind them. 661 hotel keys, 18 of which will be what we call the ball drop suites. So, they have a really cool view of Times Square and when the ball drops. There are galleries, there’s entertainment, there’s restaurants, and of course, the Historic Palace Theater with about 1,671 seats. And the Palace Theater opened in 1913, and this past May of 2022, it was raised 30 feet, which is what we’re going to be talking about today.

Jason Vesuvio (00:02:25):

So that’s it.

Christian Giordano (00:02:26):

That’s it. That’s just a small project.

Jason Vesuvio (00:02:28):

Yep. So, any project you can say the same thing about, it’s nothing without its team and certainly, while that ends up with people, I think it starts with firms. So, I’m probably going to forget some people. I feel like I’ve just maybe won best actor at the Oscars and my list is unfortunately going to be truncated, but we’ll provide links on both of our websites just in case. So, we have L&L Holding Company, Fortress and Maefield, as well as Nederlander Organization up at the top. I’m with Pavarini McGovern, like I said before, the construction manager and part of the STO Building Group. Our sister company Structure Tone here in New York is also part of our team. Manini Duffy Architects as the architect of record, Perkins Eastman on the façade, PBDW Architects on the theater interiors, Urban Foundation and Engineering, Severud Structural Engineering, Cosentini MEP Engineers, VSL International, McLaren Engineering, Wimberley Interiors—the list goes on and on and on.

Christian Giordano (00:03:34):

Yeah, I’m sure we’ve missed stuff, but we’ll put it on the website to make sure that we don’t get anybody angry. So just some quick introductions of our panel. Tony Mazzo. Tony Mazzo is the President of Urban Foundations/Engineering, LLC, and has been involved in several notable projects, a few of which include the Statue of Liberty Restoration, City Field with the New York Mets, and the restoration of six landmark theaters in Times Square. Tony is also the inventor and owns the patent for high-capacity cylindrical core beam for drilled-in caissons. Sorry, that’s a lot. <laugh> which is what was used to support the building that we’re going to be talking about today. He is a member of a number of professional organizations and holds a bachelor’s and master’s degree in civil engineering from CCNY.

Jason Vesuvio (00:04:32):

Sounds like Tony’s uniquely qualified to be on this team. We also have Joe Levi with Pavarini McGovern, Project Manager, specifically on the core and shell for TSX Broadway, with over 20 years of experience on some complex projects. His expertise includes life sciences, retail, hospitality, residential, higher ed. Joe has a BS in Environmental Science from the University of Rochester. Hi, Joe.

Christian Giordano (00:05:01):

And we have Bill Mandera. Bill is the Chief Executive Officer at Mancini Duffy, where he spends much of his time, uh, leading the firm’s efforts in new buildings, out-of-the-ground, adaptive reuse of existing buildings. Bill has been involved in several projects, including Brooklyn Army Terminal, 575 Lex, Peloton. Several projects with—more like thousands of projects here at Mancini Duffy. Bill resides in Paramus, New Jersey. It’s very important that we mentioned that. He holds a degree from New York Institute of Technology. He is an amazing drummer and has several albums out on Spotify right now.

Jason Vesuvio (00:05:42):

Yeah, I was going to say, wasn’t there just a brand-new album out right now?

Christian Giordano (00:05:45):

Just released an album, yeah.

Jason Vesuvio (00:05:46):

Unbelievable. I can’t believe we got him. <laugh>. We also have Ben Alper, Benji, who’s an Associate Principal at Severud, a structural engineering firm, very well-known obviously here in New York and elsewhere. Been with the firm since 2005 when you began your career there. You’re a licensed structural engineer in California, Nevada, as well as six other states. And you have a bachelor’s and a master’s in Civil Engineering from Cooper Union. And I understand that you made this building stand up while we made Swiss cheese of it during construction <laugh>. Is that true?

Benjamin Alper (00:06:18):

That’s our specialty.

Jason Vesuvio (00:06:20):

<laugh>. Okay. That was just handed to me. I didn’t, I didn’t write that. I can’t take credit.

Christian Giordano (00:06:23):

Can we back up a little bit and can you guys just all kind of talk about your individual roles on the project?

Joe Levi (00:06:31):

My name is Joe Levi. I’m a core and shell project manager for Pavarini McGovern. I’ve been working on TSX Broadway for the past five years now. I was involved in pre-construction, working together with Tony and Ben and Severud and, you know, many other places in conference rooms, in the Structure Tone organization, trying to coordinate the combination of the Theater lift, the temporary bracing. I was responsible for procuring some of the larger contracts, the foundation excavation contract, and infrastructure concrete, and a number of others. And over the course of the past five years, I’ve been hand in hand with these guys and also with a lot of your cohorts over at Mancini Duffy. I sit across the table from John Campbell and Anthony and Keith Lesser, and Jenna. So we’ve all been working together as a team, and I’ve been lucky enough to be on this project. And it’s honestly been a game changer in terms of just my understanding of how to approach probably what will be one of the most intense, if not the most intense repositioning projects in New York City.

Christian Giordano (00:07:41):

Awesome. Thanks, Joe. Ben.

Benjamin Alper (00:07:43):

I’m Ben Alper. I’m the Associate with Severud Associates. We are the structural engineer of record for the overall project. So, we’re kind of overseeing sort of everything that’s done. Again, you listed a whole bunch of engineering firms that worked on the project—there’s got to be at least a dozen different structural engineers, including Tony, in different aspects of it, whether it’s the foundations, the façade, the signage, all different parts. So, we worked together with everyone and really made sure that we kind of all worked together and we’re all on the same page. And that was certainly a difficult effort. And Cawsie Jijina, who’s the engineer of record from our office, the principal in charge, he really had a good vision for this project early on. And I think we started this 7/8 years ago, Tony, something like that. So, we’ve been working on it for quite some time. And it’s just great to see it to come through. And just to echo what Joe said, it’s really been a pleasure working with everyone. We’ve been doing this together all for quite some time. It’s sort of great to see it go by and walk by and see it done. Uh, so just a pretty exciting project.

Christian Giordano (00:08:51):

Awesome. Tony,

Tony Mazzo (00:08:53):

I’m the President of Urban Foundation/Engineering. I’m the foundation contractor and the design-build lift contractor for this great TSX project.

Christian Giordano (00:09:02):

Awesome, awesome. Bill?

Bill Mandara (00:09:04):

Bill Mandera. We are Mancini obviously, we’re the executive architect, and I’m the, I guess the architect of record, the guy whose licensed goes on all these things. So, there’s a great deal of trust between all the individuals here. And my job really is to make sure that our, our incredible team that Joe mentioned before with John, Tony, Keith, Jenna, a lot of people that, Anna, a lot of people that have, Rebecca, a lot of people that have came in as well, have all the resources and everything they need to do the work. Cause they’re really over there with you guys doing the Lord’s work over there. And so that’s kind of my job and my Christian, you’ll remember when this project first came to us, we both had our doubts about how real it was, and as it became more and more real,

Bill Mandara (00:09:50):

and when l became involved, we were like, oh my gosh, we’ve to really do this. And we really have to put together a team to do it. And I remember my dad was a contractor many years ago, and I was sitting down having dinner with him talking about this. I’m like, yeah, there’s this crazy project, and my father’s like, “look, take it seriously, because this could be a really big project.” At the time, I’m like, “nah, it’s never going to happen.” And here we are. So, yeah, like everybody said, it’s an honor to be part of the project.

Christian Giordano (00:10:15):

Awesome. So, we want to get into talk about the project as a whole but I think what we’d love to dive into right away is hear from all of you on the specifics of, we made reference to it in the introduction. We took this old historic Palace Theater that’s existed for what did we say here, 50 years plus? And we are elevated it up 30 feet in the air. We want to really get into detail about this. A) Why did we do this? And B) how the heck did we do this? So we’ll kind of throw it out to the panel here to get right into it.

Bill Mandara (00:10:58):

I mean, the obvious why we did it was to create this incredible space in Times Square that didn’t exist before. Literally the most heavily trafficked intersection in the world, I think is what the statistics say. By raising that theater, you’re creating space that did not exist there. So, that’s the why. Now, how is a lot more complicated. But obviously there’s a huge team of people. It’s represented in small part by some of us, but, a lot of trust that’s for sure. Given everybody had to rely on each other here.

Tony Mazzo (00:11:33):

So, Eric McGovern calls me up one day, I’m in my office in the afternoon, and he says, “I gotta ask you a question.” I said, “Sure, ask away.” He says, “I have to lift a theater in Times Square. Are you interested?” I said, “Absolutely.” He said, “You need any help?” “No, I don’t need anybody’s help” <laugh>. He says, “Tony, that’s you, Tony, I know that’s the way you are. Okay let’s do this.” And so, we embarked on a project that I think most engineers would appreciate is a once in a lifetime opportunity for sure, to do something that has never been done before. I don’t think in this country, to the magnitude that it’s been done, the scale and the location right in the heart of Times Square. Times Square is not strange to myself. As you mentioned, I’ve been involved in the Renaissance of Times Square in the ‘90s, where we refurbished maybe half a dozen landmark theaters.

Tony Mazzo (00:12:31):

And then in 1998, we actually moved the Empire Theater on 42nd Street 170 feet west to its new location, and now it is the lobby for new AMC Multiplex Theater, which is why I was qualified to at least have a conversation about the Palace Theater. It was once in a lifetime. I thought that when I was introduced as I went through this, I said this is going to be my legacy, nothing is going to top this, even though I’ve done some iconic structures. I’m a Queens boy, I was born in Queens, a Mets fan, so I did the new City Field. I did the restoration of the Statue of Liberty, you know, I thought that was the cat’s meow<laugh>. I’ve done some very cool things. I did Times Square, sorry, we did not only Times Square Tower, and other museums. We did some very iconic structures, but never was the task to lift the theater in addition to doing the new foundation for this remarkable, remarkable tower.

Jason Vesuvio (00:13:43):

Which is one of the things I think that is most interesting about this project. I mean, Christian kind of covered it a couple of minutes ago, but this is like six projects in one. There’s so much going on at one time—that dance. Especially when you think about some of the major contractors that were all on-site at the same time. You know, construction is rarely linear in a sense, but typically you’ll have excavation and foundation be replaced by super structure, and then you begin that dance up. Here you had the underground, the structure, the excavation happening at the same time while we were doing major structural demo. I mean, planning for that type of project with all of its parts is just absolutely, I would think, unheard of. What were those conversations like?

Benjamin Alper (00:14:34):

I want to give Tony the credit. What you guys didn’t mention is that literally we lowered the cellar. We had an additional cellar. While Tony was there jacking that theater up, actually right before he actually excavated out a full cellar below the theater. So, people talk about a theater lift because that’s something that’s very, very unique, but lowering it by a full cellar while you’re trying to do both things at once, it’s a whole other level. So, go ahead, Tony.

Tony Mazzo (00:15:01):

We had no choice. We had to wait about a year and a half before this structure above the existing theater would be ready to receive the 30-foot lift and tuck it into this carved out pocket.

Jason Vesuvio (00:15:16):

And talk about that a little bit too. That’s the very interesting thing.

Tony Mazzo (00:15:18):

Well, the existing str- and I think Ben can speak to this better, but I’ll put in simple terms and Ben will expand on it. There was a truss that straddled the theater a hundred feet up at the top of the theater. The new truss had to be installed 30 feet above the existing truss so that 30 feet that’s immediately above the theater could be carved out and we could tuck the theater right up into that new slide, creating basically a cavity, right?

Benjamin Alper (00:15:49):

Right, because the original theater was there, and then the hotel was built over it. They had, I’ll call it a bridge. They originally built a bridge over the original theater when they built the hotel tower above. And like Tony said, he had to slide that theater off into the pocket, but the pocket had to be created. And what we did is, like Tony said, we created these, sort of, one of a kind post-tension beams that we cast on-site, that are amongst the largest in North America. And we tensioned them in phases as we built the structure. And those are unique again, but we always get lost on the theater lift because, you know.

Joe Levi (00:16:32):

Yes, there were so many moving parts and pieces. And I think what made it even more complicated, obviously you had the theater lift element, but then you also had all these things happening in and around the theater lift. The demolition of the tower above, excavation at the same time as structural, stabilization of the existing tower. Some people don’t even know this, but there was over 168 tons of temporary steel bracing that was installed in the cellar. And many of the first conversations that I had when I was in a room with you and Benny over a Severud Associates, was how you’re going to figure rigs in and around this temporary bracing <laugh>. So, Tony, thinking out the box as he does, came up with an idea of obviously modifying your rigs to work around all these logistics.

Tony Mazzo (00:17:26):

We did. The task was to drill conventional, 36-inch diameter caissons, which are really 36-inch diameter shell holes, 60 feet down below, underneath the existing theater and hotel in maybe 16-foot headroom. And while we had some opportunities to drill those holes with conventional equipment, there were many areas where we didn’t have 16 feet. And so, my genius chief engineer, Victor Louie, came up with a design for these caisson rigs that can drill 36- and/or 42-inch diameter holes 60 feet deep within 12 feet headroom. And we called them what? The Red Dragons. We tried one and it was so successful, the owner said, “You have to make a second one right away.” And we did. And for reasons that became a benefit to the theater lift project, it was a good thing that we did.

Tony Mazzo (00:18:28):

And the reason for that is through a period of design, redesign and so forth for reasons that were evolving as the job was evolving. Remember, Joe said there were maybe half a dozen trades working at the same time. So, their work was also evolving and being put in place at the same time. So much so that my original design to lift the theater had to be put on the shelf because there was physically no room either outside the theater or within the theater to actually install the lifting system that I had originally designed.

Joe Levi (00:19:07):

And I think that’s actually important. When I walked into the original conversation, Tony had this original theater lift design in which you were lifting slabs. And I think, if you were to explain that to people.

Tony Mazzo (00:19:20):

So, you know, when you do something for the first time, your mind goes in a hundred different directions because there’s so many options. There’s no script, there’s no history. You’re going to create history. That’s exactly what we did. And in doing so, I had to make sure, alright, everybody’s going to watch us do this, so you better not screw this up. You better overthink this thing to make sure you’ve turned over every stone and looked around every corner to make sure this thing is going to be absolutely perfect. And without scrutiny, without criticism and saying, you know this is the standard of how you’re going to lift the building. Meanwhile, I haven’t done it yet. <laugh>. So, you tend to, as engineers, we tend to embrace convention and conventional designs. And that’s exactly what we started with. A conventional design that had lifting frames that could straddle the theater walls, and then a jacking mechanism that could push the theater up. Unfortunately, they told me there’s no room for any of that, Tony <laugh>.

Tony Mazzo (00:20:25):

So, we started back from scratch, and I said, “okay, look, we need three things.” And with the help of Ben, he made it very easy for us. I said, look, we’re going to need a rigid diaphragm at the base of the theater box that we’re going to lift, so that we know the theater will always stay square, and that it will be very forgiving when all the jacking points are simultaneously moved. And there might be a little bit of differential movement between one and the other. So, we built a ring beam and we employed the new third floor steel, which is very heavy steel, which is the new theater auditorium seating and that became the rigid frame. The second thing we needed was the jacking mechanism. And so, they just already told me, Tony, you can’t do it the way you said you’re going to do it.

Tony Mazzo (00:21:15):

So, okay, we went back to the blackboard.

Jason Vesuvio (00:21:17):

Can you talk just very quickly? Why?

Tony Mazzo (00:21:19):

Well, because I needed room on either side of the perimeter wall. I needed room on the inside, but unfortunately, the electrical people were putting in these big major duct banks that they needed to provide power to the tower. And on the outside, we were wrapped with scaffolding. So, all the sidewalks are occupied. So, I had no room on the outside, either. The tightest of tight sites, the tightest of tight sites. And I was trying to have a say in this, but how can I have a say when we were everyone signed up for this job to do this job simultaneously, we said, this is not going to be easy. That’s why you’re here. Okay, well that’s the rules of engagement.

Tony Mazzo (00:22:01):

I’ll take it from there. And there was only one time during this whole redesign process that I had an epiphany, and I said, “wait a minute – I got it.” Cause the only room we really had was literally underneath the theater wall itself, because we would extend those walls later on. So there was no other permanent structure going in there. But it happened to be for that year and a half that we were waiting for that cavity to be created. we also had the foundation contract to install 55, 36-inch diameter caissons, 60 feet down, most of them predominantly in the tower area, but a few distributed around the theater east side. So that, again, they’re going to create a new bridge over the new theater that’s raised 30 feet in the air. And these 36-inch diameter caissons were going to be the new supports.

Tony Mazzo (00:22:58):

And it was only when I was looking at it, I said to myself, you know what we need? We need a telescopic system to raise this theater. And I said, the easiest thing if they could sell it is a 30-foot diameter, 30-foot stroke hydraulic jack. Imagine if they sold in Home Depot <laugh>, a hydraulic jack that can extend 30 feet in the air and jack up to oh, 600 tons.

Jason Vesuvio (00:23:25):

They’re going to need a bigger store.

Tony Mazzo (00:23:28):

Well, obviously that was unheard of. But the concept was a very powerful concept. Why? Because if you look at the configuration of a 36-inch diameter caisson, it’s a steel casing, 36 inches diameter, and there’s a beam inside of it that goes all the way down to the bottom deck. You got the room. So, I say it to myself, well, this is a perfect telescopic component. If I could figure out a way to let that beam on the inside of the casing extend 30 feet up in the air out from the original casing that it’s sitting in.

Jason Vesuvio (00:24:02):

Tony, how do you get to telescopic? I mean, is it in the middle of the night while you’re tossing and turning, you’re making coffee on Sunday morning? What’s that epiphany?

Joe Levi (00:24:09):

He makes it sound like he’s changing the oil in a car.

Jason Vesuvio (00:24:12):

It really is amazing. It really is amazing. How does that come to you, that epiphany?

Tony Mazzo (00:24:16):

Well, the truth is back in the early ‘90s, the Coca-Cola bottling company of New York had a mass storage plant, for which it had 80,000 square feet of storage with 14 foot headroom. These were the post-World War II warehouses where they made warheads during the World War II. And every warehouse in Queens was 14-feet high. And they said, look, if we can raise this roof, 80,000 square foot, another eight feet, we can increase our storage by 50%, Tony, without ripping up 80,000 square foot and rebuilding. What do you think? And I looked at it and it was a simple steel frame building with open web. That’s a little technical. I said, what if we were to make those columns stay where they are? We’ll reuse them, but we’ll make them telescopic. And he looked at me, he says, “Telescopic?” I said, yeah, we’re going to let the column stretch another eight feet. And the concept was very simple. All we needed to do was sandwiches each column with two other columns, and then put a beam on the top of the outside columns, drape down some threaded rods to catch the bottom of the original column and just jacket up from the top and pull it up by its bootstraps.

Christian Giordano (00:25:35):

And then what do you do? Fill it back in?

Tony Mazzo (00:25:37):

No, no. Those two columns that straddle the original column, you weld them together and there’s your new column.

Christian Giordano (00:25:44):

Interesting.

Jason Vesuvio (00:25:45):

Engineering sounds so easy.

Christian Giordano (00:25:46):

Yeah, so easy. So Tony, I want to go back to the theater itself, right? And we can talk a little bit about the other aspects of the building, but there’s obviously a lot of prep work that goes into the theater. It had to be preserved. From what I remember, the seats came out. It was essentially stabilized at that point. You guys dig under, you create this sub foundation. You come up with the idea of the telescopic caissons. How do you physically detach the theater itself from the ground, right? Or wherever the heck it’s sitting without completely screwing up the hundred-year-old plaster inside. And then do you monitor it? How quick does it get lifted? Is it lifted in 10 minutes or is it lifted in 10 months? How does all that work?

Tony Mazzo (00:26:41):

Well, you do it very carefully. And you do it with industry standards that take careful care in surgically cutting the existing foundation away from its original foundation. And so we worked with small equipment. We worked with very skillful guys, and they were remarkable. We had to construct, as I said, we carved the ring beam underneath the theater box that’s going to be lifted. In order to do that, we had to shore the existing theater. So, whatever we’re going to do below it, whether we’re going to surgically remove a piece of the wall to infuse this ring beam, or we’re going to excavate down 30 feet from street level, which was another 18 feet from the existing cellar level, and take out 7,000 yards of earth and rock, uh, small way and conveying it through the theater basement and up through the backhouse of the theater itself, the stage area, and walk it right out 47th Street. This was all orchestrated with great planning and scheduling and coordination. You know, we spoke about, there was about four major subcontractors working at the same time. And my concern was they’re not going to give any street frontage to work from because they need it. So, we created a new street called the stage area of the Palace Theater by, we created a trestle coming in from 47th Street right across the theater stage. And it enabled heavy trucks to come in, be loaded from inside and pulled right out.

Jason Vesuvio (00:28:32):

So, a lot of concrete you poured for that, right? I mean, in and of itself. That was an impressive – you’re calling it a trestle, but it was basically you poured a new temporary slab.

Tony Mazzo (00:28:43):

Well, and a big steel trust on caissons in order to, that was the main artery to the job. It was the key to the job. There was no other way to pull trucks in from the front when three other contractors needed that front to pull their trucks in at the same time. So, we drilled these caissons to initially hold the theater up so that no matter what we did below it, that theater would stay exactly where it is. And so, the first thing we did was install these 36-inch diameters all around the theater and some of columns at the balcony columns, all of which we properly did load transfer. I want to remind you; Urban’s been doing this shoring work in New York – I’m with Urban 42 years. And I’ve been doing it ever since I got there, so this project in and of itself is the culmination of doing different facets of those mechanics that are required to both pull the theater up and eventually to mobilize it to its new location.

Joe Levi (00:29:53):

I think one of the most fascinating parts of when you were stabilizing the theater was when you hung the orchestra slab. And when you originally started talking about that, maybe five years ago, I couldn’t visualize it. But then all these mini caissons started going in within the perimeter of the theater, and you started building this enormous truss. These massive steel beams were basically rolled on top of the existing orchestra slab, pockets were cut through the orchestra slab, and within a period of almost three months, the entire orchestra slab was suspended on mini caissons below.

Tony Mazzo (00:30:36):

So, the existing columns that held up the orchestra slab could be removed because they were too short, right? Because we were going down 30 feet. So, that was the first thing we had to do, is hold up the existing orchestra level, the first-floor level, slip the seating area, hold it up from above that area, the surface of that floor, so that nothing that was going to hang there for oh few years was going to be in the way of the new construction down below.

Christian Giordano (00:31:03):

So, it hung there for a few years while you basically excavated underneath it.

Tony Mazzo (00:31:07):

That’s correct. That’s correct. But that, it was just very spacious. It wasn’t very heavy, but spacious. So, there’s a whole lattice of steel beams and hangers and many caissons in a grid to hold this floor up. That was independent of the system we needed to hold the theater up. The theater, which as you can imagine, is much heavier. 14 million pounds heavier, so there we needed larger caissons, which were the 36 inch.

Jason Vesuvio (00:31:40):

And that’s an interesting point too. Let’s throw out a few numbers. So, we lifted the theater ultimately about 30 feet in the air. So roughly 10 meters, maybe a little bit less. The theater itself is 14 million pounds, 110, 113 years old. Let’s talk a little bit about the mechanisms themselves and what I would call the control room that I remember seeing underneath the theater as it was going up. So, 34 lifting posts, 136 jacks.

Tony Mazzo (00:32:11):

Yes.

Jason Vesuvio (00:32:12):

So, you know, roughly four per?

Tony Mazzo (00:32:14):

Four per.

Jason Vesuvio (00:32:15):

And people. It wasn’t just the technology and the machinery, but it was people as well, so talk about that process.

Tony Mazzo (00:32:20):

So, we integrated old world techniques with new world technology. We always did our jacking work with a company called WB Equipment out of Jersey. And my friend Steve came through for us when he found this manifold that can control up to 48 jacking systems at the same time. So, if we had 34 that we utilized, but we had redundancy, which we needed in case some of those ports for some reason had a failure, we were able to reconnect to another port and be able to operate the lift. This manifold controlled 34 lifting stations, and it could control the speed of which the jack was extending it. It’ll measure and monitor and maintain whatever differential settlement between, uh, excuse me, differential elevation there is between them during any cycle of lift. And it could actually control the load, the maximum load that would be on one particular lifting mechanism.

Tony Mazzo (00:33:31):

It would hold it to its max and then send the load to the one adjacent to it until each one caught up. So, it was very, very sophisticated. Notwithstanding all that new world technology, I’m an old-fashioned guy, came from an old-fashioned way of doing things. So, we manned in 34 locations. We had two dock builders standing right there, making sure that the jacks extended, making sure that the plates, that the steel that was pulling up on the bottom of the core beam inside the caissons, wasn’t inhibited in any way, operating the threaded rods that obviously had to be turned down. Every time we lifted, we had to turn nuts down. And it was as simple as it was—by hand. Well, yes because we oiled everything. The system we came up with is so simple. All the dock builders had to do was sit and wait and turn hex nuts.

Tony Mazzo (00:34:31):

That’s all they had to do, right? For a total, for a sequence of five-inch lifts, we lifted in five-inch increments for which then we had to retract the jacks, run the hex nuts down, start again. And it took 25 minutes for the theater to extend, all the jacking systems to extend five inches. It took about 35 minutes to the entire system to retract and reset up for the next cycle. So, in an eight-hour shift with some, okay, let’s stop, let’s look, let’s measure, let’s make sure the monitoring has done its job and that everything is working, and everything is according to what we planned, we were able to average about two and a half feet per eight-hour shift. And so, this whole 30-foot lift was done in two phases. We lifted approximately 18 feet in the first phase, and then a few weeks later, we lifted the other approximately 12 feet.

Joe Levi (00:35:35):

Which is remarkable because originally, we were talking about a two-month period for the entire duration. So, you contracted that period into, what was it really? It would’ve been only two and half weeks.

Jason Vesuvio (00:35:53):

Insane. I’ve heard this story so many times. It never ceases to amaze me.

Christian Giordano (00:35:53):

Not in that level of detail.

Narrator (00:35:58):

In this next segment, the group discussed how the structure reacted to the initial lift. Worker safety was a top priority for the entire team throughout the project, and all falling brick and debris was safely contained.

Joe Levi (00:36:10):

So you know, I feel like we skipped over a few things and Tony does that obviously because in his world, you know, this is all easy as turning a few nuts. But, going back, there was a point in time where the entire theater was suspended, all the excavation had been completed. So, you can imagine this entire theater sitting on lifting posts and small interior caissons, exterior larger 36 inch diameter caissons with your posts within them. And the cellar was down approximately, what was it? Almost 25 feet? 28 feet. So, you would actually be able to go in below the theater and look up and see almost the entire space cavity below the theater was, anybody who’d walk into the cellar at that point knew how remarkable it was to see a theater suspended in air.

Tony Mazzo (00:37:08):

When we started, you couldn’t see daylight because the theater walls that remained were down to approximately the existing cellar level. By the time we finished, you could see 18 feet of daylight below those same walls that started 13 feet below.

Jason Vesuvio (00:37:24):

Unbelievable. Let’s go back to that maybe that very first night. I was talking to Eric McGovern, Pavarini McGovern’s, CEO about this. And, he recalls the two of you, and there may have been more people, but he recalls the two of you, Tony, testing the system the night before. He called it, the night before the Hollywood Lift and wanted to shake or be sure that the foundation was cut and removed. And I just said, you know, what was that like? And he described the sounds. He said, there were just these amazing pings and things were shaking, and you could hear concrete and steel rubbing against one another. But his line was, it was like we were in the belly of a whale. What do you remember about that night? And the same goes for the three of you when you were first seeing the lift. Go ahead, Tony.

Tony Mazzo (00:38:17):

It was a really interesting experience. We anticipated the pings that you were talking about are the movements of the steel girders and their connections, the stressing of the threaded rods that were hanging the lifting posts. The crunching of masonry as it rolled past its joint. The crumbs were the crumbling bricks that were coming loose and falling. The theater was talking to us, and it was saying, it’s okay, we’re going to do this. It’s fine, you know, everything that I’m talking to you. Everything that you hear is what you anticipated hearing. And, it was absolutely magical.

Christian Giordano (00:39:11):

Wow. Let talk a little bit about the building itself, right? And the fact that it’s a new building, but not really. It’s also a renovation because we kept portions of the building. I remember an early on conversation, Benji, you were telling us you guys have to remember that you’ve got to keep X amount of the slab left. We’re poking holes through this. You have to keep it. And I remember leaving that initial meeting so stressed out, like how are we going to do this? There’s no way. I mean, we’re talking about keeping tiny little one-inch pieces or every little half inch counts. Why did we need to keep the slab? And then how did we go about kind of making, as we made light of it, Swiss cheese of it? But we really did at the end of the day.

Benjamin Alper (00:39:59):

Bill, why don’t you address why we needed to keep the slab and I’ll address the easier part.

Bill Mandara (00:40:03):

Fair enough. Yeah, Christian, you got nervous. I was looking up countries with no extradition treaties. The reason we did that was because the project is not a new building. It’s an Alteration Type 1 and in order for us to remain an Alteration Type 1, we had to keep 25% of the floor area. And why that’s important is because the existing structure was overbuilt. I don’t recall the exact number of how much, but it was a significant amount. Whereas if we did not retain that floor area, we would’ve had to build a much smaller building, which would’ve made the project financially infeasible. We had a lot of, and I think this is why Benji punted this one to me, right? We had a lot of meetings

Bill Mandara (00:40:48):

On like what does four area mean? There’s some people that took it as a literal, it’s people you throw around the name retain slab, which is actually a misnomer because nowhere in the zoning code anywhere does it say anything about its slab. It says floor area. But, you know, there was a lot of different opinions on that and what that means, whether it’s area that existed before. So, if the area that existed before had a big opening, well, that’s what the area was, and you’re keeping it, because again, I couldn’t find any countries where I wanted to live that spoke English and had no extradition treaties, we went with the most conservative approach on that, which was to keep more so of it than we need. Um, we had a good bank of it available – several thousand square feet beyond what we needed to be over the 25%.

Bill Mandara (00:41:38):

And, it’s a good thing because this is where Ben comes in. There were times where there were areas, I mean, there was a lot of work that was done between John Campbell from our off office, the demolition contractors and multiple engineers, including Severud, where we’d say, okay, we’re keeping this chunk of slab here. Okay, great. And they’re like, yeah, but we need to poke holes in there to get temporary structures in there, or to get, get lifts through or things like that. So, okay, that doesn’t work. Um, and then we would go back and we got it, we’d get it all perfectly done, and then we’d go over there, demo something. They’d be like, oh, well, this slab is a hunk of garbage and falling apart. Um, so we’d be like, rats, good thing we have some in the bank. So, we thankfully ended with some square footage in the bank, which makes me feel better.

Benjamin Alper (00:42:25):

Yeah. I’d say part of the challenge also is that we weren’t just trying to retain the slab, but in many places, we were reusing it for different usage that had a higher live demand. So, we were taking a hotel floor and turning it into a restaurant, so we couldn’t just try to retain it in place. We actually had to re retain it and strengthen it. Um, so we had a lot of different, um, ways of doing that. A lot of times with, taking a set let’s say an eight-inch slab and either pinning an additional four inches on top of it to strengthen it to make it effectively a 12-inch slab, and a lot of different techniques. But another thing that Bill said, as we had these means and methods issues, and we were trying to sort of erect the steel in the middle of the existing floor slabs. So, it wasn’t just like, you know, you had an open space and you’d bring the steel in. We were fighting over, literally, we’d fight over every hole. Every hole they’d put in, they’d put in to bring a steel column and, and brace up. We would fight about how big it was. We’d sit there with all the engineers in the room and PMG kind of the arbitrator, and we’re just like, yeah, no, that’s too big. Cut down an inch or two.

Joe Levi (00:43:29):

Just as there were 170 tons of steel just for temp bracing in the cellar, there was another 170 plus tons of steel in the West tower for temp bracing as we were making these holes. So, you know, obviously presented a challenge, not just in the construction, but in the demolition sequence as well. So as all these slabs were being, you know, a sliver removed here, a small sliver here, we had to install bracing and then figure out a way to rebuild the new slab or beam or truss around these temporary braces.

Benjamin Alper (00:44:01):

Yeah, I mean, I’d say one thing about this job is that people all the way through, and Tony touched on this, all the way through as the job changed and the job was changing around us, I’d say day by day, and you had Pavarini and you had Tony and all the subs – no matter what they had thrown at them, they didn’t just try and say, okay, I had this idea and I’m going to stick with it. I’m going make it. They reimagined the idea and they took it and they sort of started new and said, okay, let’s do what’s the best. I don’t care that I had this idea. Let’s start from the beginning. And sort of like, and every day, almost every day, it’s something seemed like we had a new challenge and people would reimagine it from the beginning. And sort of,

Joe Levi (00:44:34):

We were working hand in hand with Shapiro Associates, also was Severud constantly on a day by day basis trying to determine the extent of interferences and work around them and try and find a solution. Megan Kirk, your field engineer, she did a fantastic job of working together with us. And I think that was only way it was accomplished. To be able to find and solve and almost immediately find solutions so that we can keep going. You know, when you have 125 guys from Sorbara onsite, there’s no way you’re going to stop for a day. You just have to keep going.

Tony Mazzo (00:45:05):

Speaking of re-imagining things, the third component of successfully lifting the theater is making sure it doesn’t fall out into Times Square.

Christian Giordano (00:45:14):

Yes. That makes sense. That was my next question. So now how do you finish it?

Tony Mazzo (00:45:19):

Okay. As I told you earlier, there was no real estate on the outside because we were wrapped in scaffolds to build what I had originally conceived as temporary frames that had vertical rails on it that I can attach to the theater. And the theater would virtually be guided by this exterior frames. But

Jason Vesuvio (00:45:43):

You, you had what, five, six inches in between, right?

Tony Mazzo (00:45:46):

There was no room at all. Because the scaffolds occupied all the outside space. So once again, in the middle of night, I had an epiphany and I realized if you can, the original tower that straddled the theater had sheer walls surrounding it in three corners. And so, I said to myself, there’s the frame. All I need to do is design a guide rail to attach to a vertical guardrail that goes 30 feet up the, up these sheer walls and connect it to that base, that ring beam, rigid diaphragm. So, we literally grabbed the theater by its waist and kind of lifted it straight up <laugh>,

Jason Vesuvio (00:46:32):

Straight up, like Dirty Dancing style or the Notebook or something?

Bill Mandara (00:46:35):

More like Simba.

Jason Vesuvio (00:46:36):

Circle of life. Amazing. So, one of the things that, and you know, the project is still going on, the restoration of the theater is happening right now.

Benjamin Alper (00:46:48):

I think we’re basically done. So <laugh>.

Jason Vesuvio (00:46:50):

Yeah. <laugh>, you guys did the hard part. But, and maybe this is more for Bill or Joe, but talk about the inside of the theater and the prep there. I mean, for those listeners who are outside of New York City, this theater’s a New York City landmark, and there are some stringent requirements around that. Talk about how you, not so much the restoration itself, which is, you know, beginning or ongoing now, but the prep work, sort of the interior skeleton and what you needed to do.

Joe Levi (00:47:19):

So, prior to the theater lift, obviously there was a whole bunch of other consultants that were engaged, which presented a few more challenges to the team. And I think we worked around them quite well. As a matter of fact, I think Tony is probably responsible for, you know, getting us across that hurdle. There were a number of things going on at any one time, including vibration monitoring, temporary stabilization of the exterior facade, stabilization of the interior plaster. So, they went around and did an entire assessment and took photographs of the entire theater. And a consultant also went around to determine what was stable, what was not. If it wasn’t stable, they tried to stabilize it using scaffolding systems. The entire arch way was, for the most part, stabilized and there was a temporary partition that was placed on it.

Joe Levi (00:48:09):

Because, as Tony told you before, Tony’s main means of access was the theater stage. So, there was this major gap, obviously the stage area, which would allow moisture and humidity to come into the theater. So, we had constant temperature, humidity controls running from day one. As soon as we cut the power, we had temp power going into the theater, running humidifiers, dehumidifiers, heaters, coolers, you name it, with someone there 24/7 even up to this day. So, this was obviously a massive undertaking. I mean, there was just nothing small to it. Everything around the theater was stabilized. Tony, you could probably speak a little bit more to any of the foundational elements.

Christian Giordano (00:48:57):

There is the subway going past there too.

Jason Vesuvio (00:48:59):

That’s true.

Joe Levi (00:49:00):

It was, you know, but that wasn’t as much of a concern except for when we were doing, um, foundation work around the subway area. The neighbors were obviously very concerned as to how this would work. I think Tony could speak to that a little bit.

Tony Mazzo (00:49:15):

But the pigeons on the roof didn’t know the theater was moving.

Jason Vesuvio (00:49:20):

Just a normal day for them.

Christian Giordano (00:49:21):

That’s great. That was the mission of it.

Bill Mandara (00:49:23):

Yeah. I mean, you guys spent how long just stabilizing the interior of that and again, the amount of agencies not to mention, not the least of which was the owner, the actual owner of the theater, who had a lot of concerns about that.

Joe Levi (00:49:37):

We were stabilizing up until the day of the lift. Even after, so you, you know, once Tony did his test lift, we found some areas where there were some walls, which were actually not landmarked walls, which needed to be removed. And we were concerned that they were going to fall during the lift. So, we went through that night and took out some small partitions. So, everything was happening live, and at the moment, it was a nonstop performance from day one when Tony came up with this concept, you know, up to about the end of the theater lift.

Jason Vesuvio (00:50:07):

That’s an important point, Joe. It’s not that the entire interiors of the theater were landmark. There were certain sections.

Joe Levi (00:50:12):

That’s right. So, there were certain parts and we had to pay close attention to them. So, the original entrance into the Palace Theater, which extended from 7th Avenue through the West Tower of the old DoubleTree Hotel into the theater, that wasn’t actually a landmark space. So that was able to be removed. So now the lobby, when you walk into the theater, is going to extend from, or start from 7th at 47th Street and you’re going to take an escalator up to the third floor.

Bill Mandara (00:50:44):

I mean, that’s one of the things too is that, because we called it, we still called it the theater box, the actual landmark stuff and actual pieces that were in there. There was a whole other set of challenges, which was how that interacts with the new building. To your point, Joe, the new lobby that we created on the third floor, all the front of house, all the back of house items, because even though we have this historic theater, we’re subject to all the current rules and regulations for restrooms and life safety and all those things. So having that interact with the new modern building was quite a bit of a challenge as well. Not to mention, you know, you could do a whole other podcast on the acoustic concerns with this project.

Joe Levi (00:51:22):

I was just going to say – so, there’s an acoustic separation between the theater and what is going to be the future stage that projects out the Times Square on the third floor. So, there’s obviously constraint that you’re aware of, you know, that are pretty high when it comes to, you know, the performances happening at the same time on the stage on Broadway and a performance possibly happening at the same time within the box of the theater.

Bill Mandara (00:51:49):

And it could be big performances. I mean, you could have a full-scale Broadway musical going on in that theater, and you could have potentially like U2 out there playing, who knows? I mean, I’m dating myself with the reference.

Jason Vesuvio (00:52:00):

And a lot of advertising happening on the LED around the podium and up the building.

Bill Mandara (00:52:04):

And at the same time, you could have a retail tenant or some experiential tenant blasting music or God knows what as well. So, all those things have to happen outside of each other. And without hearing each other.

Jason Vesuvio (00:52:17):

As a New Yorker, I’m glad it’s happening in Times Square, not my neighborhood.

Christian Giordano (00:52:21):

And I’ll say this too. We spent months on just stairs alone on this project.

Bill Mandara (00:52:28):

Oh my gosh. On stairs alone.

Christian Giordano (00:52:29):

I know that’s because one of our guys, Keith, he was on stair duty for months and months and months. And it seems kind of silly and I don’t think I really understood why until he explained it. Look, you were basically creating a new state-of-the-art brand-new tower that had all updated egress challenges that had to go down, around, through and not into, past, you know, an existing historic theater. I mean, so how do you get from that top floor all the way down through that theater or not through that theater, around that theater? I mean, we calculated stuff within, quarters of an inch, which as an architect and instructional engineer, we laugh at that stuff when it’s on a piece of paper. Like someone puts a quarter inch dimension on a piece of paper, we laugh at them. I go, that’s ridiculous.

Bill Mandara (00:53:19):

You laugh, I yell.

Christian Giordano (00:53:20):

Nobody’s going to take that seriously. But that’s what it was. That was what it was down to at that point. We had every little speck of room counted.

Bill Mandara (00:53:29):

I mean, we had multiple egress studies and a lot of outside consultants, double, triple checking everything we did because not only you have to get everybody out of there safely, in God forbid, some bad event, but you also have to make it so somebody can’t walk out of their hotel room and then just like open up the door in their underwear at a Broadway show, which was, there was a lot of conversations about that, quite frankly. So, it was definitely, yeah, lots of work on stairs and egress, but we’re good.

Christian Giordano (00:53:57):

And then last couple things about the building, just talk a little bit, whoever wants to take it, about those doors, those digital doors.

Joe Levi (00:54:08):

So, the digital doors, which extend from the third floor almost up to the balcony of the fifth floor, um, open up to a stage which is going to be part of the TSX entertainment

Bill Mandara (00:54:22):

Yep. The stage that’ll open up right onto Times Square where they can do the NFL draft or the New Year’s Eve thing or whatever.

Joe Levi (00:54:28):

And, so that stage being obviously probably one of the most integral parts of the entertainment space has that acoustical separation that we talked about earlier. So that’s why, you know, we have those line partitions, double line walls, all surrounding the entertainment area.

Bill Mandara (00:54:50):

And those doors, they will be, well, they are because they’re installed, the frameworks installed for them now, they’re the world’s largest operable LED doors. And they open inward, and you could have, and I forget the amount of time, but it’s a very short amount of period of time in which they can open up. And you could have a performer that could be performing inward towards an audience, or just turn around and perform outward toward, towards Times Square, you know, in literally in seconds.

Jason Vesuvio (00:55:17):

Is this the first building ever of its kind that’s truly just a living marketing tool?

Bill Mandara (00:55:22):

I believe it is. I mean, the amount, again, a whole different conversation, but the amount of time that we spent on LED systems, whether it be the main LED signage or the actual building, incorporating all those pucks into the entire facade and the programming and the software that goes into it, and the technology that goes into that is astounding. So yeah, it literally is, it’s a living marketing machine.

Christian Giordano (00:55:47):

Yeah. And meant to also, from what I understand, cross the street and go to some neighboring buildings in terms of content and be able to move around, which is pretty cool.

Joe Levi (00:55:56):

I actually was able to attend one of the fireside chats over at TSX Entertainment, and I found it just remarkable the concept that they came up with, of being able to include live productions and also recording studios, possibly all surrounding, you know, a new way of delivering entertainment. It’s something that’s really never been done before, but I give them a lot of credit for going in that direction.

Bill Mandara (00:56:24):

It’s, it’s going to be pretty amazing.

Christian Giordano (00:56:26):

So, as we begin to wrap up, what’s next for the remainder of the project as it finishes up? What’s next for, Tony, someone like you? Are you going to be moving an entire skyscraper down the block at some point? What are some of the other things that you’re all thinking?

Tony Mazzo (00:56:46):

I’m thinking I’m not going to get a call like that again.

Jason Vesuvio (00:56:49):

Once in a lifetime, right?

Tony Mazzo (00:56:51):

But I’ll be ready to take the call if it does come through.

Christian Giordano (00:56:53):

I love it. That’s great. And what about the building? What’s next for the building in terms of finishing?

Tony Mazzo (00:56:58):

So, we spoke about the theater lift. So, after the theater lift was completed, Tony had to complete the cellar slab because while the theater was being lifted, only the ground floor slab was in place, at which point he fell back, he completed the ground floor slab. And we demoed part of the existing steel truss, which is above the theater. And then during the final lift, we demolished the remainder of the steel truss, which allowed us to build and extend all the north cantilever terraces on the 9th, 10th, and 11th floors. All of which are hung below the box girder, which is quite remarkable.

Jason Vesuvio (00:57:33):

Which is unbelievable in and of itself to actually see that done.

Joe Levi (00:57:39):

Because if you’re in a suite above the theater, you’re actually suspended on the largest PT bridge in probably North America.

Jason Vesuvio (00:57:51):

It’s four floors, right, Ben that hangs from that transfer?

Benjamin Alper (00:57:55):

Yep. It’s, yeah, it’s I think one of the largest PT girders in North America.

Christian Giordano (00:57:59):

What does PT mean?

Benjamin Alper (00:58:01):

Post-tensioning. Post-tensioning. We have sort of bridge cabling strands embedded in concrete, and then we pull them and as we pull them, it actually lifts the girder up and it counteracts the gravity force.

Jason Vesuvio (00:58:12):

And it’s unusual for New York City, some of our listeners in other parts of the country, right?

Benjamin Alper (00:58:16):

Right, exactly. Outside, no big deal. Outside of New York City, it’s a lot more common. Post tension slabs, post tension beams. It was special in New York City. And one of the big reasons is because the site that we’re working with, uh,

Jason Vesuvio (00:58:28):

Density

Benjamin Alper (00:58:29):

Is just so tight. Trying to bring in steel and build trusses was just. It was a study we do with PMG at the beginning of the job. And the original building was done steel and then we converted it to post-tension concrete when they just looked at the feasibility of doing it. So

Joe Levi (00:58:43):

Yeah, there’s actually, and I have some facts here I’ll throw out because they’re interesting. There’s over 210,000 linear feet of post tension cable. 0.6 diameter, 36 tendons, 43 tendons. Were stressed to over 2 million pounds of force using the largest PT jack in North America. So, this jack really is, it was exported from Europe to the United States, and it had to be hung by a crane because it weighs over 7,300 pounds.

Benjamin Alper (00:59:12):

Some of those strands had to be brought in for over from overseas.

Joe Levi (00:59:16):

That’s right.

Benjamin Alper (00:59:18):

Our caissons also are some of the largest, actually the largest that they make. The steel that we have. And then your system, um, your, uh, manifold system, is from Singapore.

Tony Mazzo (00:59:27):

Singapore.

Benjamin Alper (00:59:27):

Brought in special for the job. So this is not, you know.

Joe Levi (00:59:30):

Very atypical.

Bill Mandara (00:59:32):

I’ve been on construction sites since I was 14 years old. I was there the day you were pouring that post tension girder. I’ve never seen that many concrete trucks in one place. And literally I’ve been on construction sites since I was 14 years old.

Benjamin Alper (00:59:43):

On the hottest day of the summer, it had to be the one day we poured that post. For another time.

Joe Levi (00:59:51):

So, we actually didn’t lock off the cables in tension, in final tension until the building was topped off. So, there was an entire sequencing to that whole post tensioning. And what was interesting about it was, I think no one was quite sure if the building was going to move or not.

Benjamin Alper (01:00:08):

What do you mean? I knew exactly what was – we told you upfront. I’m not sure if you believed us or not. And at the end we hit it dead on.

Joe Levi (01:00:17):

He did. He was right on. It was a half inch shot.

Jason Vesuvio (01:00:10):

So right now, we’re restoring the theater, we’re fitting the hotel out. What else are we doing right now?

Joe Levi (01:00:28):

That’s it. We’re working on critical building infrastructure, doing interior fit-outs, finalizing the hotel room fit-outs, and working our way towards TCO the summer of 2023.

Christian Giordano (01:00:40):

Amazing. Well, is there anything we haven’t covered that you guys want to jump in and talk about here before we wrap up?

Tony Mazzo (01:00:50):

I’d just like to say that I was asked by many people why in your right mind would you do something like this? And I said, well, first of all, because I think I can. But more importantly, I wanted this to be an inspiration to the younger, to the industry at large, the younger generation, to inspire them to realize that if they look deep into their skillset, anything is possible. And that sometimes you just have to step out of your comfort zone and realize what your full potential could be in order to do things that under normal circumstances you’d never be asked to do. So, I really did this more to inspire the younger generation and to give credibility to this great industry of ours.

Christian Giordano (01:01:41):

Awesome. I love it. Well, on that note, Tony, Joe, Benji, Bill – thank you so much for being our guests here on the Building Conversations and Anti-Architect podcasts. To see and read more about TSX, the best place to start is the website, which is TSX Broadway. There’s a lot of articles. There’s news, releases, there’s interviews, there’s all of the social media channels, the Instagram, the Facebook, Twitters – there’s even a TikTok. I’m not exactly sure what’s on that, but there’s a lot of information out there. And then, yeah, come visit it. If you’re in New York in the next year and a half or so, it’ll be ready for someone to stay there and come watch Bill’s band play on the stage one day as well.